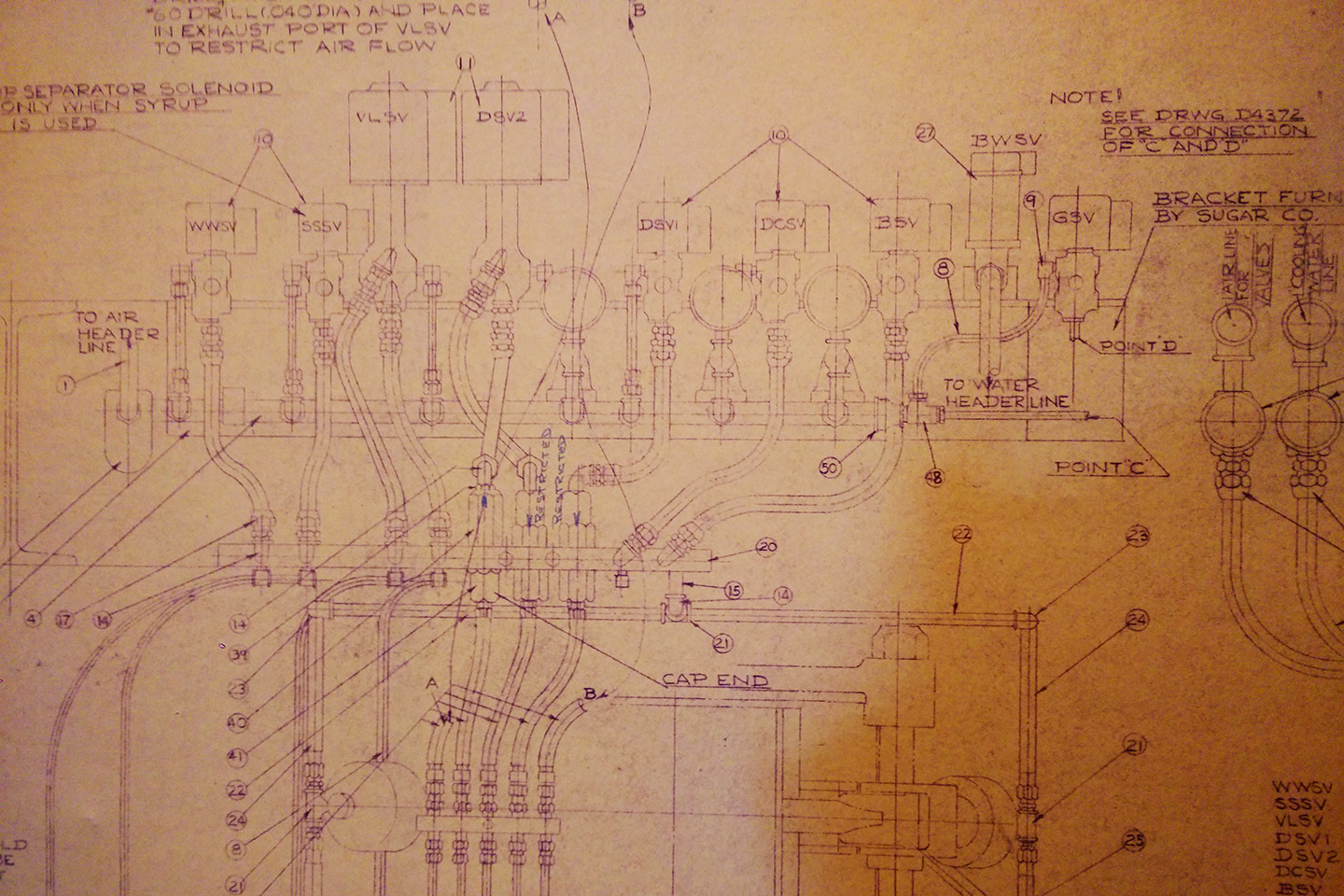

Innumerable intricate lines and notations on sheet after sheet of mimeograph paper were unintelligible to me. “Sucrose Separator Solenoid Valve,” “Note! See Drwg D4372 for connection of ‘C’ and ‘D,’” “Unit Piping Diagram for Automatic Centrifugal.” The dates on the diagrams ranged as early as the 1910s going up to the 1970s or so. I found them rotting away in the machine shop drawers of an abandoned factory.

The Williamsburg Domino Sugar Refinery was the largest sugar processing facility in the world when it was established on the banks of New York City’s East River in 1882. Needless to say, sugar refinement would change over the next 120 years of the factory’s operation, and so did its machines. From the outside, there was no way to tell that the human-sized floors held vast machinery, creating a unified production system snaking through the ten-story building.

The diagrams suggested that someone could make sense of it all. And not just make sense of it, but fix it! Someone had to keep the machines going. The diagrams connected the delicate mass of metal and plastic to soft hands and precise tools. Some diagrams show tremendous things smaller, like multi-floor sifters and cookers. Others make tiny things bigger, like intricate leavers and circuitry. Some are creased down the middle, possibly from someone folding it up to go to another shop or to the site of the machine itself. Others are pristinely flat.

Some are concerned with the precise dimensions of all parts, like the Drive End Steel Trunion. Others have no dimensions but label each piece by a catalog number for easy replacement. Some label all weldings holding a particular component together, like the Split Basket Valve Assembly For Straddle Valve Lifter. Others focused on the circuitry, like Vacuum Pan No 1.

I wandered the empty factory in awe. I wasn’t supposed to be there, but I found my way in with some friends. We discovered the machine shop on a lower floor during our third or fourth visit. It was disturbingly wet, not wet like upper floors that were covered in thick sucrose goo. The shop was just wet. Something had been dripping into it for a long time. Workbenches were corroded. One cabinet of drawings was ruined completely. Parts of the factory smelled so sweet it was nauseating. But not here. There were no windows, no natural light. It was moist and musty. The heavy smell was of slow growing mold. A weak fluorescent ceiling light was on, which struck me as odd. Only later did I realize that it was likely lit because the guards passed through on rounds. You’d never think a place in this condition had guards, but it did.

The diagrams would have rotted away if left them in the machine shop. I took the ones still in good condition. Most are in tubes in my archives. Some have become framed wedding gifts for couples that met in Brooklyn. Six now act as wallpaper behind the couch in my reading nook. I like the imagine that someday many years from now, a history buff will walk into my nook and marvel with mixed delight and horror at the pilfered historic documents suck up with wallpaper paste.

When I found the machine shop, the diagrams represented things that still existed on the floors above me, though they had stopped being repaired years ago. The factory ended production 2007 and was sold to a developer in 2010. I went rooting around the place in late 2012 after the site changed hands from the first incompetent developer to an accomplished, determined one. Destruction was imminent. Historic landmarking in New York only protects the outside of buildings. Very rarely do the insides get of cially preserved, too. I think there is an old bar or club inside the Woolworth Building that is landmarked, and there is a funny little museum on Staten Island that’s so proud of their interior landmarking. With the Domino Sugar Refinery, the innards were not landmarked, though their vastness and complexity carried just as much historic significance as the shell that held them together. Maintaining landmarked buildings is a lot of work. Keeping Domino going while it was active was a lot of work, too. The diagrams fill me with equal parts sadness as they do nerdy delight. The machines are all gone now.